THE MAASAI OF EAST AFRICA

A Maasai village

INTRODUCTION

The Maasai tribe (or Masai) is a unique and popular tribe due to their long preserved culture which reside in both Tanzania and Kenya, living along the border of the two countries. Despite education, civilization and western cultural influences, the Maasai people have clung to their traditional way of life, making them a symbol of African culture.

ORIGIN AND LOCATION

No one knows where the Maasai come from. It is thought to be somewhere north along the Nile – or maybe beyond, further East. In one theory, it says, like the Falasha of western Ethiopia, the Maasai are jewish: a long lost tribe of Israel.

However, It is thought that the Maasai’s ancestors originated in North Africa, migrating south along the Nile Valley and arriving in Northern Kenya in the middle of the 15th century. They continued southward, conquering all of the tribes in their path, extending through the Rift Valley and arriving in Tanzania at the end of 19th century. As they migrated, they attacked their neighbors and raided cattle. By the end of their journey, the Maasai had taken over almost all of the land in the Rift Valley as well as the adjacent land from Mount Marsabit to Dodoma, where they settled to graze their cattle.

Maasai location in East Africa

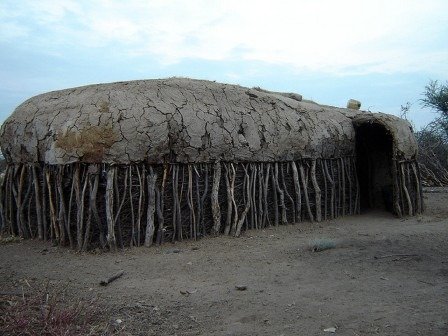

Maasai house

Manyatta, A Maasai village

Today, Maasai homeland is bounded by Lake Victoria to the west and Mount Kilimanjaro to the east. Maasailand extends some 310 miles (500 kilometers) from north to south and about 186 miles (300 kilometers) at its widest east-west point.

Lake Manyara, Ngorongoro, Tarangire and Serengeti parks in Tanzania and The Amboseli, Nairobi, Masai Mara, Samburu, Lake Nakuru and Tsavo National Parks in Kenya, all stand on what was once the territory of the Maasai tribes.

FOLKLORE

Maasai legends and folktales tell much about the origin of present-day Maasai beliefs. These stories include their ascent from a crater, the emergence of the first Maasai prophet-magician (Laibon), the killing of an evil giant (Oltatuani) who raided Maasai herds, and the deception by Olonana of his father to obtain the blessing reserved for his older brother, Senteu (a legend similar to the Biblical story of Jacob and Esau).

One origin myth reveals much about present-day Maasai relations between the sexes. It holds that the Maasai are descended from two equal and complementary tribes, one consisting strictly of females, and the other of males. The women’s tribe, the Moroyok, raised antelopes, including the eland, which the Maasai claim to have been the first species of cattle. Instead of cattle, sheep, and goats, the women had herds of gazelles. Zebras transported their goods during migrations, and elephants were their devoted friends, tearing down branches and bringing them to the women who used them to build homes and corrals. The elephants also swept the antelope corrals clean. However, while the women bickered and quarreled, their herds escaped. Even the elephants left them because they could not satisfy the women with their work.

According to the same myth, the Morwak—the men’s tribe—raised cattle, sheep, and goats. The men occasionally met women in the forest. The children from these unions would live with their mothers, but the boys would join their fathers when they grew up. When the women lost their herds, they went to live with the men, and, in doing so, gave up their freedom and their equal status. From that time, they depended on men, had to work for them, and were subject to their authority.

LANGUAGE

Maasais speak Maa, a Nilotic ethnic language from their origin in the Nile region of North Africa. The origins of Maa have been traced to the east of present-day Juba in southern Sudan. More than twenty variants of Maa exist. The Maasai refer to their language as Olmaa.

RELIGION

The supreme being and creator is known as Enkai (also called Engai), and serves as the guardian over rain, fertility, love and the sun. It was Enkai who gave cattle to the Maasai people. Neiterkob is a minor deity, known as the mediator between God and man. Olapa is the Goddess of the Moon, married to Enkai. The myth is that they were fighting one day when Olapa, being a short-tempered woman, inflicted Enkai with a grievous wound. To cover up his wound, he cast a spell which enabled him to shine so brightly, that no one could look straight at him and see his shame. Enkai then took his revenge by hitting Olapa back and striking out one of her eyes. This can be seen today, when the moon is full.

SOCIAL WELFARE SYSTEM

Their social welfare system, for instance, covers the sharing, or community ownership, of the walking wealth, land, housing, food, and under a fairly permissive sexual code even each other. They are free to sleep where, when, and with whom they please so long as they confine themselves to their age mates, obtain consent and avoid breaking set of rules guarding gainst in-breeding.

The Maasai life’s imagery has some sections of which each corresponds to the character and status of the Maasai man in each of the distinct divisions, or age-grades, of his life.

In infancy, he is in “state of grace”, a close communication with God, symbolized by a tuft of hair grown on the crown of his head.

Then, as soon as he can toddle, he is sent out with the calves and lambs, the cockade on his scalp is gone and his hair begins to grow.

At any time from 13 to 17 his ‘boyhood’, ayiokisho , is ended abruptly in a painful circumcision ritual at which he stays silent and brave while his parents writhe and scream for his in a simulated agony.

After that he becomes a worrrior- recruit, proving his courage and endurance in long expeditions with his age-mates; in blooding his spear on young animals and birds and perhaps in provoking fights with the Moran of other sections.

Eventually, a company of these boys is allowed to set up a Manyatta as junior warriors and, if the weather is good and there is plenty of help at home, free to spend the next 2 or 3 years doing anything or nothing as they please until serious responsibilities arrive after the graduation to senior worrior, at the eunoto

The man is then at the centre of his society. He directs the stock and range management business of the community, takes part in defense, security and perhaps local government affairs, and is free. At the age of about 30, they retire from moran to junior elder. When this happens he moves out of Munyatta into a family enclosure, enkang, and, at an unspecified time, bocomes a senior elder, usually via a meat eating ritual, called ol ng’esher

From then on his prestige and influence increase until he eventually retires with the other members of his age-set. He might then be a consultant on all temporal and spiritual affairs as a ‘venerable elder’ until he dies and is left out in bush for swift disposal by the elements and scavenging hyenas. There is nothing more; no ‘after life’ in eternal green fields among his ancestors. This is not part of the Maasai’s religious imagery- or at least, they ‘don’t know’ or ‘can’t be sure’

In this simple and clear age grade system, a maasai knows exactly where he stands in his local community and in the age grade.

The Maasai are one of the very few tribes who have retained most of their traditions, lifestyle and lore

7. RITES OF PASSAGE

Life for the Maasai is a series of conquests and tests involving the endurance of pain. For men, there is a progression from childhood to warrior-hood to elder-hood. At the age of four, a child’s lower incisors are taken out with a knife. Young boys test their will by their arms and legs with hot coals. As they grow older, they submit to tattooing on the stomach and the arms, enduring hundreds of small cuts into the skin.

Ear piercing for both boys and girls comes next. The cartilage of the upper ear is pierced with hot iron. When this heals, a hole is cut in the ear lobe and gradually enlarged by inserting rolls of leaves or balls made of wood or mud. Nowadays plastic film canisters may serve this purpose. The bigger the hole, the better. Those earlobes that dangle to the shoulders are considered perfect.

Circumcision (for boys) and excision (for girls) is the next stage, and the most important event in a young Maasai’s life. It is a father’s ultimate duty to ensure that his children undergo this rite. The family invites relatives and friends to witness the ceremonies, which may be held in special villages called imanyat. The imanyat dedicated to circumcision of boys are called nkang oo ntaritik (villages of little birds).

Girls must endure an even longer and more painful ritual, which is considered preparation for childbearing. (Girls who become pregnant before excision are banished from the village and stigmatized throughout their lives.) After passing this test of courage, women say they are afraid of nothing.

Circumcision itself involves great physical pain and tests a youth’s courage. If they flinch during the act, boys bring shame and dishonor to themselves and their family. At a minimum, the members of their age group ridicule them and they pay a fine of one head of cattle. However, if a boy shows great bravery, he receives gifts of cattle and sheep.

Maasai woman with short hair

Guests celebrate the successful completion of these rites by drinking great quantities of mead (a fermented beverage containing honey) and dancing. Boys are then ready to become warriors, and girls are then ready to bear a new generation of warriors. In a few months, the young woman’s future husband will come to pick her up and take her to live with his family.

After passing the tests of childhood and circumcision, boys must fulfill a civic requirement similar to military service. They live for up to several months in the bush, where they learn to overcome pride, egotism, and selfishness. They share their most prized possessions, their cattle, with other members of the community. However, they must also spend time in the village, where they sacrifice their cattle for ceremonies and offer gifts of cattle to new households. This stage of development matures a warrior and teaches him nkaniet (respect for others), and he learns how to contribute to the welfare of his community. The stage of “young warriorhood” ends with the eunoto rite, when a man ends his periodic trips into the bush and returns to his village, putting his acquired wisdom to use for the good of the community.

Through rituals and ceremonies, including circumcision, Maasai boys are guided and mentored by their fathers and other elders on how to become a warrior. Although they still live their carefree lives as boys – raiding cattle, chasing young girls, and game hunting – a Maasai boy must also learn all of the cultural practices, customary laws and responsibilities he’ll require as an elder.

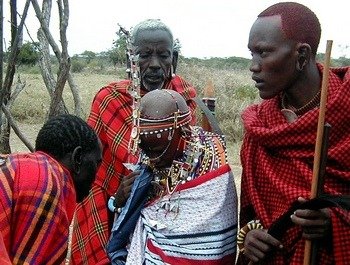

Moran, Maasai warriors.

Between the ages of about 14 and 30, young men are traditionally known as Morans. During this life stage they live in isolation in the bush, learning tribal customs and developing strength, courage, and endurance—traits for which Maasai warriors are noted throughout the world

Warriors

The warrior is of great importance as a source of pride in the Maasai culture. To be a Maasai is to be born into one of the world’s last great warrior cultures. From boyhood to adulthood, young Maasai boys begin to learn the responsibilities of being a man (helder) and a warrior. The role of a warrior is to protect their animals from human and animal predators, to build kraals (Maasai homes) and to provide security to their families.

Maasai warriors (young men) engage in special jumps around during the dance. This dance is part of how they find a mate. The highest jumper gets the girls

Maasai children enter into a system of “age-sets” with peers where various life stages, such as circumcision, are marked with ritual and ceremonies. At the age of 14, girls are initiated into adulthood through an official circumcision ceremony known as Emorata.

Young Maasai warrior (a junior Moran) with headdress and markings

Presently, the female circumcision ritual is outlawed and its use is diminishing from the Maasai women’s culture. Young Maasai girls are still taught other functional roles like how to build houses, make beadwork, and cook and clean their homes, by their mothers and older women. When they come of age, their parents “book” a warrior from a respectable clan as an appropriate husband for their daughter.

RELATIONSHIPS

A father blessing his daughter

Women can only marry once in a lifetime, although men may have more than one wife (if enough cows are owned, they may have more than one at a time). At the wedding ceremony held by the Masai (Maasai) the father of the bride blesses her by spitting on her head and breasts. Then she leaves with her husband.

Each child belongs to an “age set” from birth. To control the vices of pride, jealousy, and selfishness, children must obey the rules governing relationships within the age set, between age sets, and between the sexes. Warriors, for example, must share a girlfriend with at least one of their age-group companions. All Maasai of the same sex are considered equal within their age group.

Many tensions exist between children and adults, elders and warriors, and men and women. The Maasai control these with taboos (prohibitions). A daughter, for example, must not be present while her father is eating. Only non-excised girls may accompany warriors into their forest havens, where they eat meat. Although the younger warriors may wish to dominate their communities, they must follow rules and respect their elders’ advice.

Did you know?

Traditionally the Maasai men measures their wealthand prestige in terms of number of cattle one has – and their male heirs!

Traditionally Maasai people of Africa do not bury their dead. Burials are believed to harm the soil and is reserved only for some chiefs. Most dead bodies are simply left outside for scavengers.

LIVING CONDITIONS

By Western standards, Maasai living conditions seem primitive. However, the Maasai are generally proud of their simple lifestyle and do not seek to replace it with a more modern lifestyle. Nevertheless, the old ways are changing.

Maasai women repairing a house

Shelter covered in cattle dung for waterproofing

Maasai and their love of cattle

Since the Maasai lead a semi-nomadic life, their houses are loosely constructed and semi-permanent. They are usually small, circular houses built by the women using mud, grass, wood and cow-dung. The men build the fences and sheds for the animals.

Formerly, cowhides were used to make walls and roofs of temporary homes during migrations. They were also used to sleep on. Permanent and semi-permanent homes resembling igloos were built of sticks and branches plastered with mud, and with cow dung on the roofs. They were windowless and leaked a great deal. Nowadays, tin roofs and other more modern materials are gradually transforming these simple dwellings.

FAMILY LIFE

The Maasai are a patriarchal society; men typically speak for women and make decisions in the family. Male elders decide community matters. Until the age of seven, boys and girls are raised together. Mothers remain close to their children, especially their sons, throughout life. Once circumcised, sons usually move away from their father’s village, but they still follow his advice. Girls learn to fear and respect their fathers and must never be near them when they eat.

A Maasai elder

In Maasai society, the elders are fathers of families, sages, medicine men, spiritual counsellors and judges. They are proud to be the conscience of society, guardians of its laws and its spiritual traditions and always try to observe discipline and work hard

The Maasai love speeches and the elders know many proverbs and sayings

A person’s peers (age-mates) are considered extended family and are obligated to help each other. Age-mates share nearly everything, even their wives. Girls are often promised in marriage long before they are of age. However, even long-term engagements are subject to veto by male family members.

CLOTHING

Young women and girls, and especially young warriors, spend much time on their appearance. Styles vary by age group. The Maasai excel in designing jewelry. They decorate their bodies with tattooing, head shaving, and hair styling with ochre and sheep’s fat, which they also smear on their bodies. A variety of colors are used to create body art.

Women and girls wear elaborate bib-like bead necklaces, as well as headbands and earrings, which are colorful and intricate. Jewelry plays an important role in courtship.

Maasai clothing varies by age, sex, and place. Traditionally, shepherds wore capes made from calf hides, and women wore capes of sheepskin. The Maasai decorated these capes with glass beads. In the 1960s, the Maasai began to replace animal-skin with commercial cotton cloth. Women tied lengths of this cloth around their shoulders as capes (shuka) or around the waist as a skirt.

A Maasai woman and A Maasai girl wearing on their finest

Every Maasai does not wear the exact same clothes, but there are a few common traits. For example, most Maasai wear the color red because it symbolizes their culture and they believe it scares away lions.

For example, red means bravery and strength, blue represents the color of the sky and rain, white shows the color of a cow’s milk, green symbolizes plants, orange and yellow mean hospitality and black shows the hardships of the people.

The Maasai color of preference is red, although black, blue, striped, and checkered cloth are also worn, as are multicolored African designs. Elderly women still prefer red and dye their own cloth with ochre (a natural pigment). Until recently, men and women wore sandals made from cowhides; nowadays sandals and shoes are generally made of tire strips or plastic.

FOOD

The Maasai depend on cattle for both food and cooking utensils (as well as for shelter and clothing). Cattle ribs make stirring sticks, spatulas, and spoons. Horns are used as butter dishes and large horns as cups for drinking mead.

The traditional Maasai diet consists of six basic foods: meat, blood, milk, fat, honey, and tree bark. Wild game (except the eland), chicken, fish, and salt are forbidden. Allowable meats include roasted and boiled beef, goat, and mutton. Both fresh and curdled milk are drunk, and animal blood is drunk at special times—after giving birth, after circumcision and excision, or while recovering from an accident. It may be tapped warm from the throat of a cow, or drunk in coagulated form. It can also be mixed with fresh or soured milk, or drunk with therapeutic bark soups (motori). It is from blood that the Maasai obtain salt, a necessary ingredient in the human diet. People of delicate health and babies eat liquid sheep’s fat to gain strength.

A Maasai girl milking the cow

Maasai man drinking blood

Honey is obtained from the Torrobo tribe and is a prime ingredient in mead, a fermented beverage that only elders may drink. In recent times, fermented maize (corn) with millet yeast or a mixture of fermented sugar and baking powder have become the primary ingredients of mead.

The Maasai generally eat two meals a day, in the morning and at night. They have a dietary prohibition against mixing milk and meat. They drink milk for ten days—as much as they want—and then eat meat and bark soup for several days in between. Some exceptions to this regimen exist. Children and old people may eat cornmeal or rice porridge and drink tea with sugar. For warriors, however, the sole source of true nourishment is cattle. They consume meat in their forest hideaways (olpul), usually near a shady stream far from the observation of women. Their preferred meal is a mixture of meat, blood, and fat (munono), which is thought to give great strength.

Maasai warriors prepare to roast meat over an open fire

Many taboos (prohibitions) govern Maasai eating habits. Men must not eat meat that has been in contact with women or that has been handled by an uncircumcised boy after it has been cooked.

EDUCATION

There is a wide gap between Western schooling and Maasai traditional education, by which children and young adults learned to overcome fear, endure pain, and assume adult tasks. For example, despite the dangers of predators, snakes, and elephants, boys would traditionally herd cattle alone. If they encountered a buffalo or lion, they were supposed to call for help. However, they sometimes reached the pinnacle of honor by killing lions on their own. Following such a display of courage, they became models for other boys, and their heroics were likely to become immortalized in the songs of the women and girls.

Over the years, school participation gradually increased among the Maasai, but there were few practical rewards for formal education and therefore little reason to send a child to school. Formal schooling was primarily of use to those involved in religion, agriculture, or politics. Since independence, as the traditional livelihood of the Maasai has become less secure, school participation rates have climbed dramatically.

CULTURAL HERITAGE

The Maasai have a rich collection of oral literature that includes myths, legends, folktales, riddles, and proverbs. These are passed down through the generations. The Maasai also compose many songs. Women are seldom at a loss for melodies and words when some heroic action by a warrior inspires praise. They also improvise teasing songs, work songs for milking and for plastering roofs, and songs with which to ask their traditional god (Enkai) for rain and other needs.

DIVISION OF LABOUR

Labor among traditional herding Maasai is clearly divided. The man’s responsibility is his cattle. He must protect them and find them the best possible pasture land and watering holes. Women raise children, maintain the home, cook, and do the milking. They also take care of calves and clean, sterilize, and decorate calabashes (gourds). It is the women’s special right to offer milk to the men and to visitors.

Children help parents with their tasks. A boy begins herding at the age of four by looking after lambs and young calves, and by the time he is twelve, he may be able to care for cows and bulls as well as move sheep and cattle to new pastures. Girls help their mothers with domestic chores such as drawing water, gathering firewood, and patching roofs.

SPORTS

While Maasai may take part in soccer, volleyball, and basketball in school or other settings, their own culture has little that resembles Western organized sports. Young children find time to join in games such as playing tag, but adults find little time for sports or play. Activities such as warding off enemies and killing lions are considered sport enough in their own right.

RECREATION

Ceremonies such as the eunoto, when warriors return to their villages as mature men, offer occasions for parties and merriment. Ordinarily, however, recreation is much more subdued. After the men return to their camp from a day’s herding, they typically tell stories of their exploits. Young girls sing and dance for the men. In the villages, elders enjoy inviting their age-mates to their houses or to rustic pubs (muratina manyatta) for a drink.

CRAFTS AND HOBBIES

The Maasai make decorative beaded jewelry including necklaces, earrings, headbands, and wrist and ankle bracelets. These are always fashionable, though styles change as age-groups invent new designs. It is possible to identify the year a given piece was made by its age-group design. Maasai also excel in wood carvings, and they increasingly produce art for tourists as a supplemental source of income

THE MAASAI TRIBE TODAY

The effects of modern civilization, education and western influence have not completely spared this unique and interesting tribe. Some of the Maasai tribe’s deep-rooted culture is slowly fading away. Customs, activities and rituals such as female circumcision and cattle raiding have been outlawed by modern legislation. Maasai children now have access to education and some Maasai have moved from their homeland to urban areas where they have secured jobs.

However, the Maasai’s authentic and intriguing culture is a tourist attraction on its own. You can see the Maasai people and experience Maasai culture while on a safari. The Safari also provide an ideal opportunity for participants to take part in the Maasai dance and buy traditional Maasai jewelry, art and crafts to take home as souvenirs.